Colour vision deficiency

Colour vision deficiency is the inability to distinguish certain shades of colour. The term "colour blindness" is also used to describe this visual condition, but very few people are completely colour blind.

Colour vision is possible due to photoreceptors in the retina of the eye known as cones. These cones have light-sensitive pigments that enable us to recognize colour. Found in the macula (the central part of the retina), each cone is sensitive to either red, green or blue light (long, medium or short wavelengths). The cones recognize these lights based on their wavelengths. Normally, the pigments inside the cones register different colours and send that information through the optic nerve to the brain. This enables us to distinguish countless shades of colour. But if the cones don't have one or more light-sensitive pigments, they will be unable to see all colours.

Most people with colour vision deficiency can see colours. The most common form of colour deficiency is red-green. This does not mean that people with this deficiency cannot see these colours altogether, they simply have a harder time differentiating between them, which can depend on the darkness or lightness of the colours.

Another form of colour deficiency is blue-yellow. This is a rarer and more severe form of colour vision loss than just red-green deficiency because people with blue-yellow deficiency frequently have red-green blindness, too. In both cases, people with a colour-vision deficiency often see neutral or grey areas where colour should appear.

People who are totally colour deficient, a condition called achromatopsia, can only see things as black and white or in shades of grey. Colour vision deficiency can range from mild to severe, depending on the cause. It affects both eyes if it is inherited and usually just one if it is caused by injury or illness.

Causes & risk factors

Usually, colour deficiency is an inherited condition caused by a common X-linked recessive gene, which is passed from a mother to her son. But disease or injury that damages the optic nerve or retina can also cause loss of color recognition. Some diseases that can cause color deficits are:

- Diabetes.

- Glaucoma.

- Macular Degeneration.

- Alzheimer's disease.

- Parkinson's disease.

- Multiple Sclerosis.

- Chronic alcoholism.

- Leukemia.

- Sickle Cell Anemia.

Other causes for colour vision deficiency include:

Medications. Drugs used to treat heart problems, high blood pressure, infections, nervous disorders and psychological problems can affect colour vision.

- Ageing: The ability to see colours can gradually lessen with age.

- Chemical exposure: Contact with certain chemicals—such as fertilizers and styrene—have been known to cause loss of colour vision.

In many cases, genetics cause colour deficiency. About 8% of white males are born with some degree of colour deficiency. Women are typically just carriers of the colour-deficient gene, though approximately 0.5% of women have colour vision deficiency. The severity of inherited colour vision deficiency generally remains constant throughout life and does not lead to additional vision loss or blindness.

Symptoms

A person could have poor colour vision and not know it. Quite often, people with red-green deficiency aren't aware of their problem because they've learned to see the "right" colour. For example, tree leaves are green, so they call the colour they see green. Also, parents may not suspect their children have the condition until a situation causes confusion or misunderstanding.

Early detection of colour deficiency is vital since many learning materials rely heavily on colour perception or colour-coding. That is one reason the AOA recommends that all children have a comprehensive optometric examination before they begin school.

Diagnosis

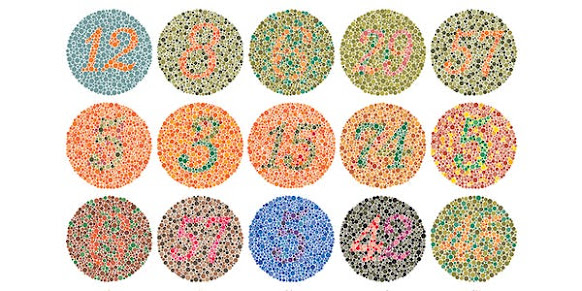

Colour deficiency can be diagnosed through a comprehensive eye examination. The patient is shown a series of specially designed pictures composed of coloured dots, called pseudoisochromatic plates. The patient is then asked to look for numbers among the various coloured dots. Individuals with normal colour vision see a number, while those with a deficiency do not see it.

On some plates, a person with normal colour vision sees one number, while a person with a deficiency sees a different number. Pseudoisochromatic plate testing can determine if a colour vision deficiency exists and the type of deficiency. However, additional testing may be needed to determine the exact nature and degree of colour deficiency.

Treatment

There is no cure for inherited colour deficiency. But if the cause is an illness or eye injury, treating these conditions may improve colour vision. Using specially tinted eyeglasses or wearing a red-tinted contact lens on one eye can increase some people's ability to differentiate between colours, though nothing can make them truly see the deficient colour.

- Organizing and labelling clothing, furniture or other coloured objects (with the help of friends or family) for ease of recognition.

- Remembering the order of things rather than their colour. For example, a traffic light has red on top, yellow in the middle and green on the bottom.

Colour vision deficiency can be frustrating and may limit participation in some occupations, but in most cases, it is not a serious threat to vision. With time, patience and practice, people can adapt. Although in the very early stages, several gene therapies that have restored colour vision in animal models are being developed for humans.

Comments

Post a Comment